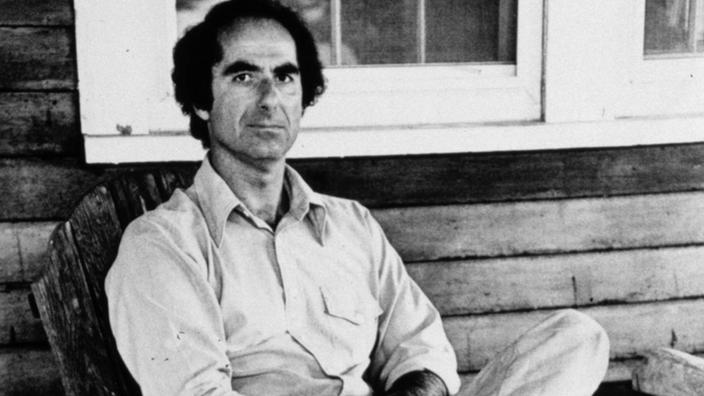

Portnoy is far from my favorite Roth book: I find that it curdles, albeit meaningfully, as it goes along, its jokes wearing thin as the adult Alex Portnoy remains trapped by his sexual fixations - a narcissist "locked up in me," as he admits. Officially, I told myself, I was there not because I wanted to meet "Philip" but because I wanted to understand how Roth the novelist had birthed Portnoy's Complaint. Anyone could tramp, as I soon did, into the Manuscripts Room of the Library of Congress and, ten minutes later, peruse some dark muddled fantasy that Roth had committed to paper, then chosen never to publish. And odder still to imagine that the notoriously guarded author, who moved to the countryside after the success of Portnoy's Complaint, had been converted by his archive into a different sort of person - a chummy and amenable fellow, on call and happy to submit to my devices. It was odd to think that Roth, despite being interred at Bard College Cemetery on (at a ceremony where Jewish rituals were expressly forbidden), was alive and well and living at the Library of Congress. His language was charmingly informal, reflecting an archivist's intimacy with his materials, but also a little jarring. Would I need to specify in advance which boxes - among the 300 Roth left, measuring 122.6 linear feet - I wished to consult? Not at all, he told me: "Philip is on site so we can call him up and get him to you in five minutes." A month ago, I was on the phone with a librarian in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, inquiring about the papers of Philip Roth.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)